I recently hosted a cordage gathering at my house with Tanya, a new friend. If you asked me a month ago if this was something on my radar, I would not have any context or reference point aside from a passing interest in cordage. How did I get from there to here?

Hanji, silk, and tule cords and fabric scraps after the cordage gathering

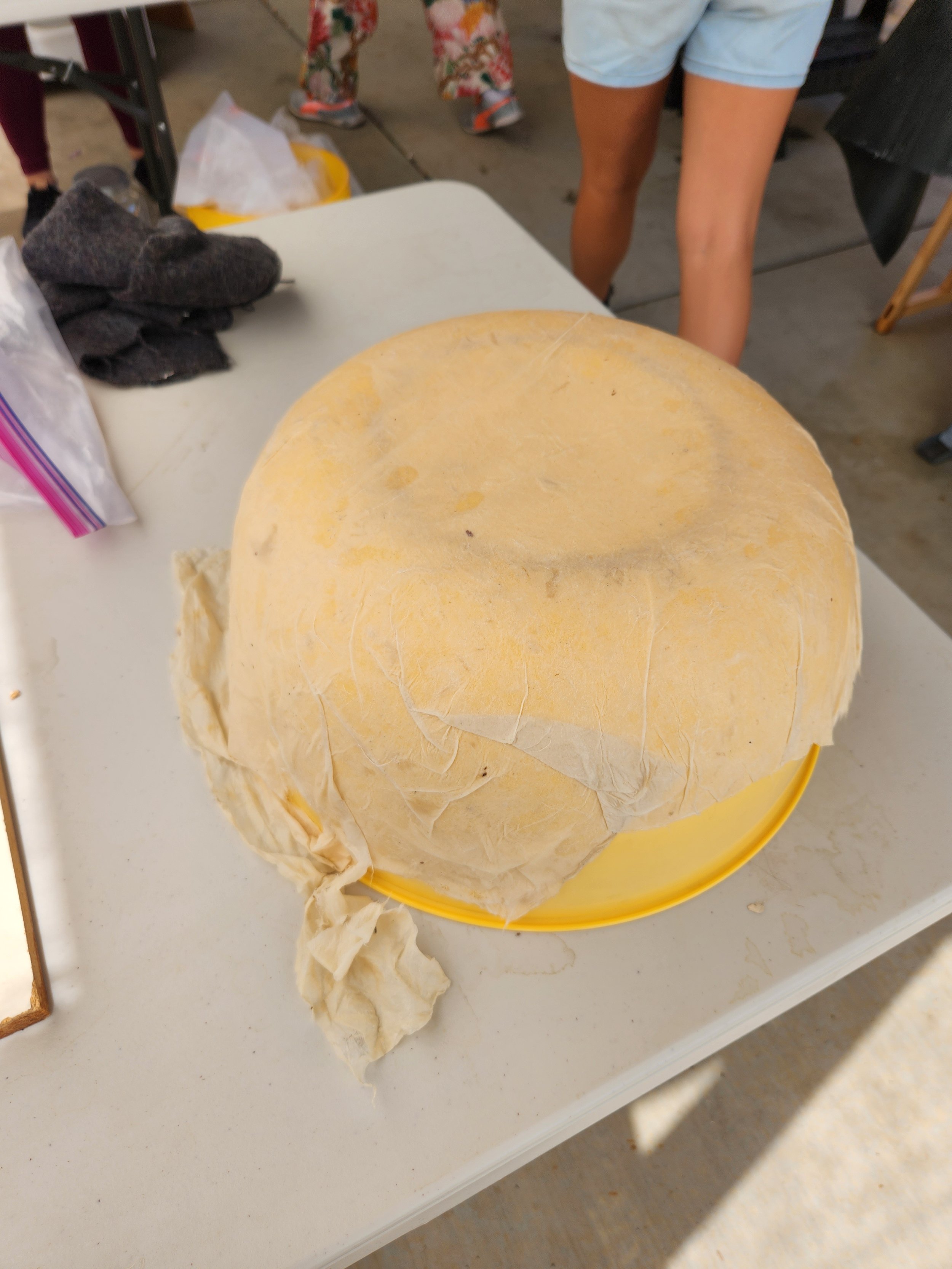

This season I've been trying to look for the openings and go with the flow. One opening was prompted by the kids' annual school Winter Faire, which requires all 1st and 2nd grade families to each donate 30-40 handmade items that are then sold as a fundraiser. I had just been out to Cache Creek Conservancy, where I learned about the work of Diana Almendariz and her community work, cultural work, and craft work with the tule plant. I also had signed up for a tule mat making workshop, to learn about the use of tule for ecological restoration of the wetlands. While at the conservancy with Tanya, she grabbed some tule soaking nearby and showed me how to make a simple cord:

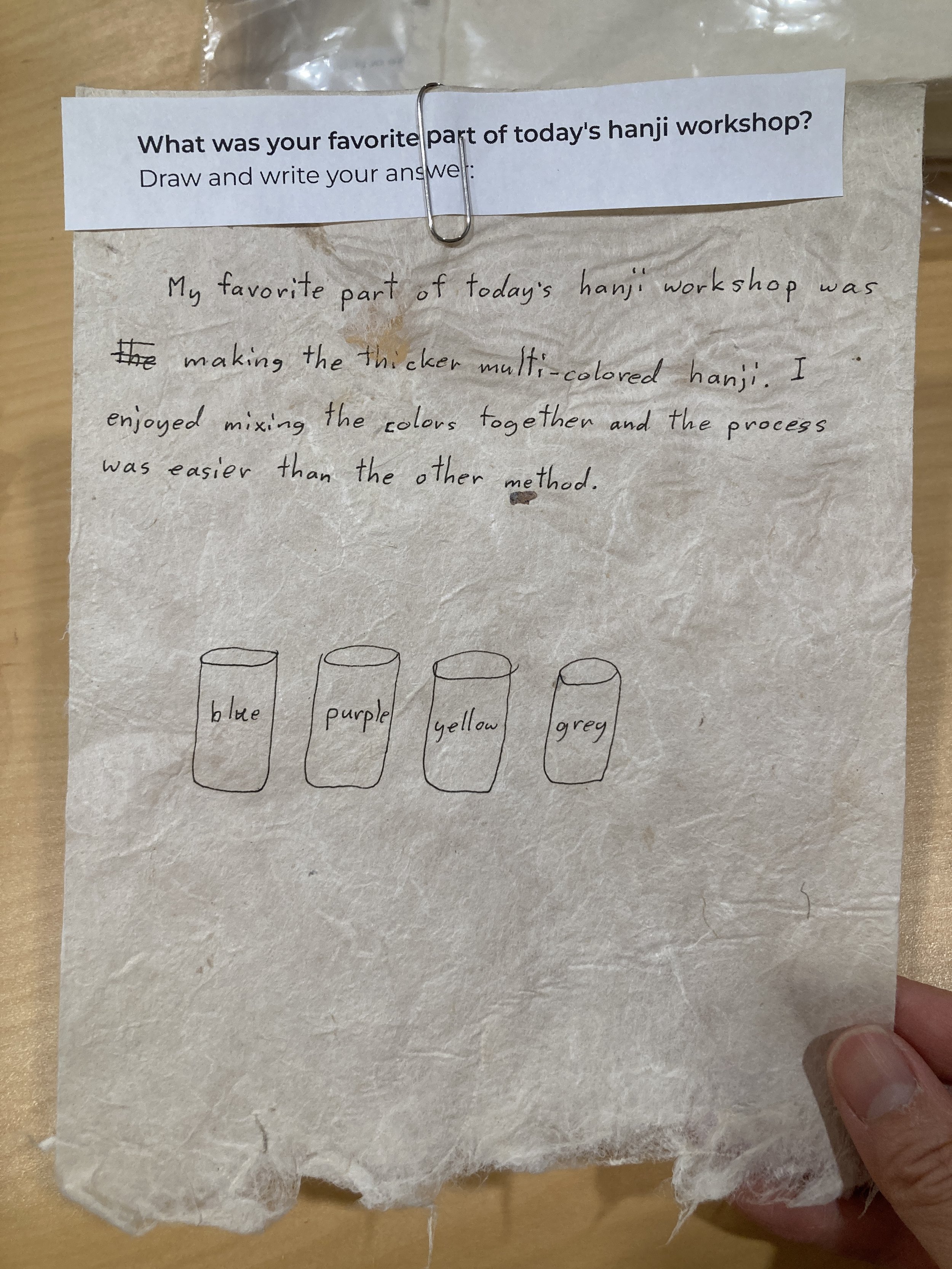

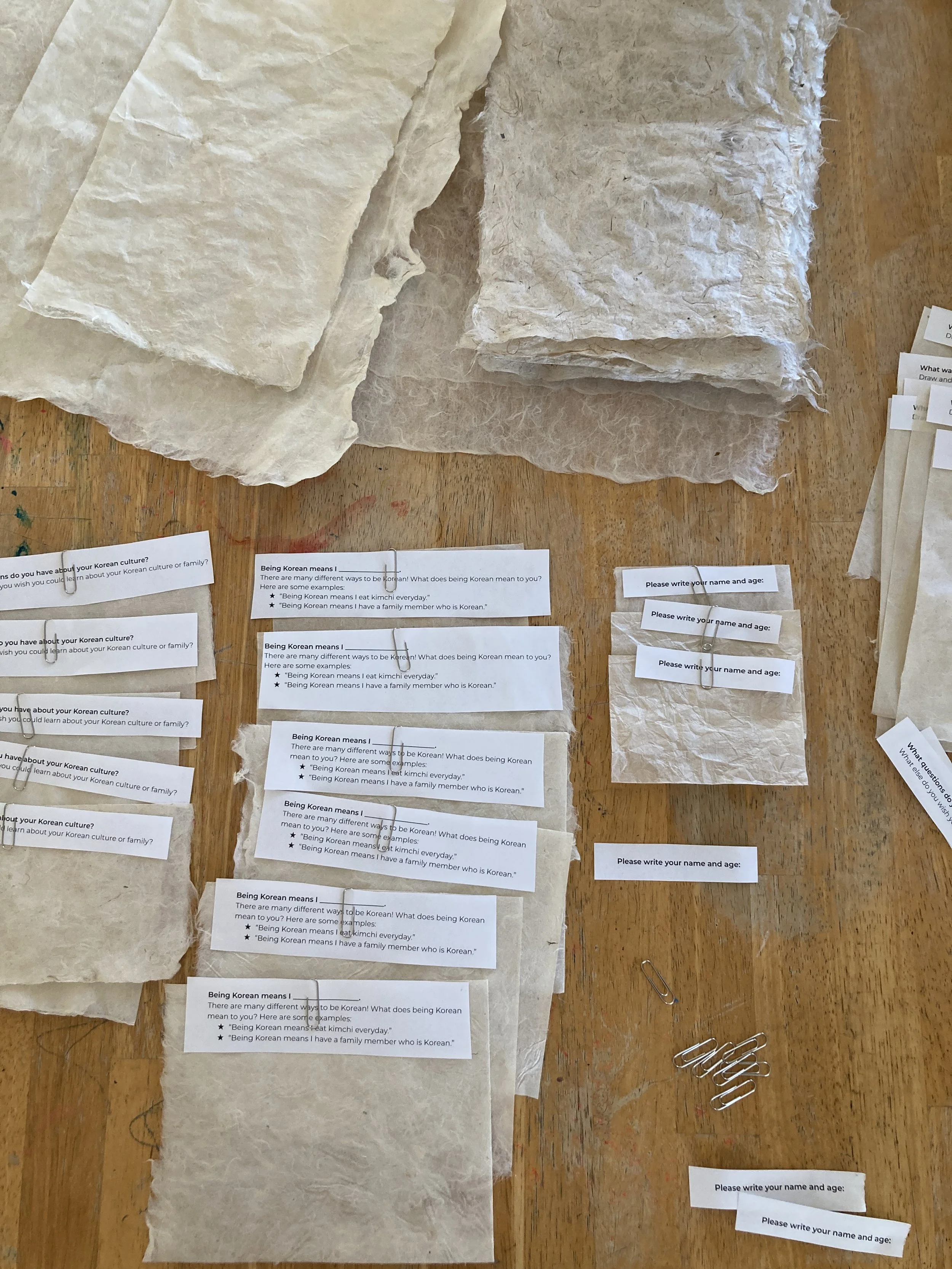

I’ve also been part of an Asian American women & femme circle facilitated by Jayoung Ahn, called Reclaiming Us. During one session, Jayoung led us in a visualization exercise to connect with our lineage: past, present, and future. As a response to this exercise, we were then prompted to create something with our hands.

[This is actually part of a longer story that still feels raw/sensitive/vulnerable. I share it here with tenderness and also uncertainty with how relevant it is to this post about cordage. Always I worry about taking up unnecessary/excessive space. But this is the beauty of self-publishing my own writings. I can determine how much space I want to give to whatever I want! Still, I'm putting this in brackets... Here is the story: One night last month, I had acute, intense stomach pain so bad that I ended up in the ER. I've lived all my life with chronic stomach pain, but this was unlike anything I had experienced before. After several hours at the ER, the doctor eventually diagnosed me with a UTI and sent me home. By then the pain had subsided. A few days later at my follow-up appointment, my PCP said it was not actually a UTI, but probably "just" a really bad stomach ache. She asked if I was under any stress and suggested dietary changes, but only after I kept prodding her with questions. She got defensive when I questioned the UTI diagnosis, quick to justify the ER doctor's opinion. The whole experience felt surreal, and I questioned if the pain I had experienced was real. Later that week my mom casually mentioned that my paternal grandmother used to have really bad stomach aches, so severe that my dad has strong childhood memories of banging on the neighborhood doctor's door in the middle of the night. Apparently these memories are what inspired my dad to become a physician. I also met with my somatic therapist, who told me that many of her Korean clients suffer chronic stomach pain. (in fact my brothers, my mom and I all suffer from chronic GI issues.) She suggested that this pain could be stuck, unmetabolized grief that is not moving through the body. I share this story with caution and hesitation because my former self (and people currently in my life, including family members) would receive this story with a hard eye roll. I used to defer to Western doctors and medicine as bearers of Truth; now I feel that they are utterly ill-equipped to care for the whole self. I used to feel very little connection to my ancestors; now I feel an opening, a connection to my grandmother, through pain - a visceral pain that I know intimately, that I've known in my body all my life. I used to dismiss the mind-body-spirit connection; now I know that it is true, I grieve for the lost years that I spent completely disconnected to my body and the knowledge and wisdom that it holds.]

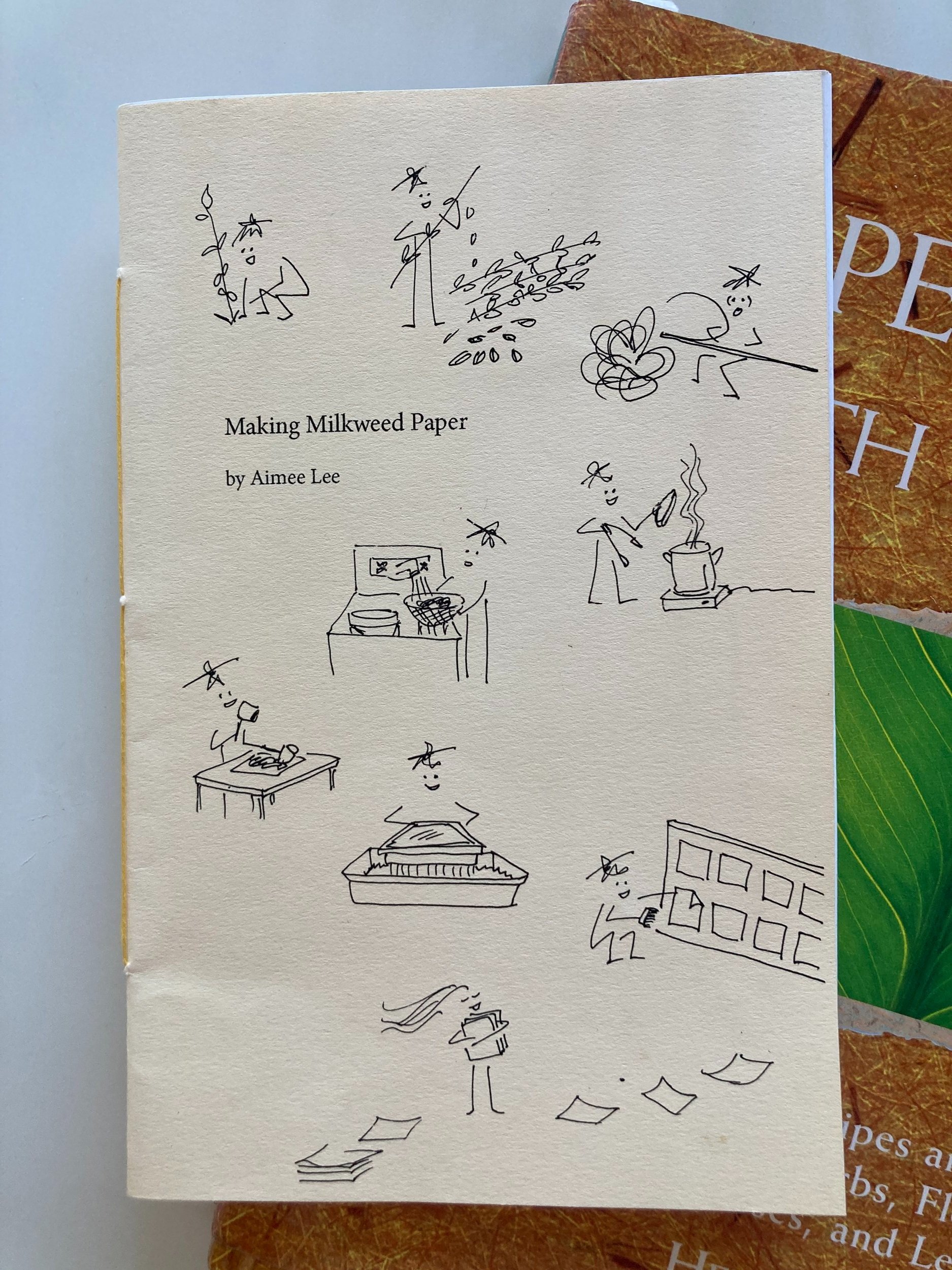

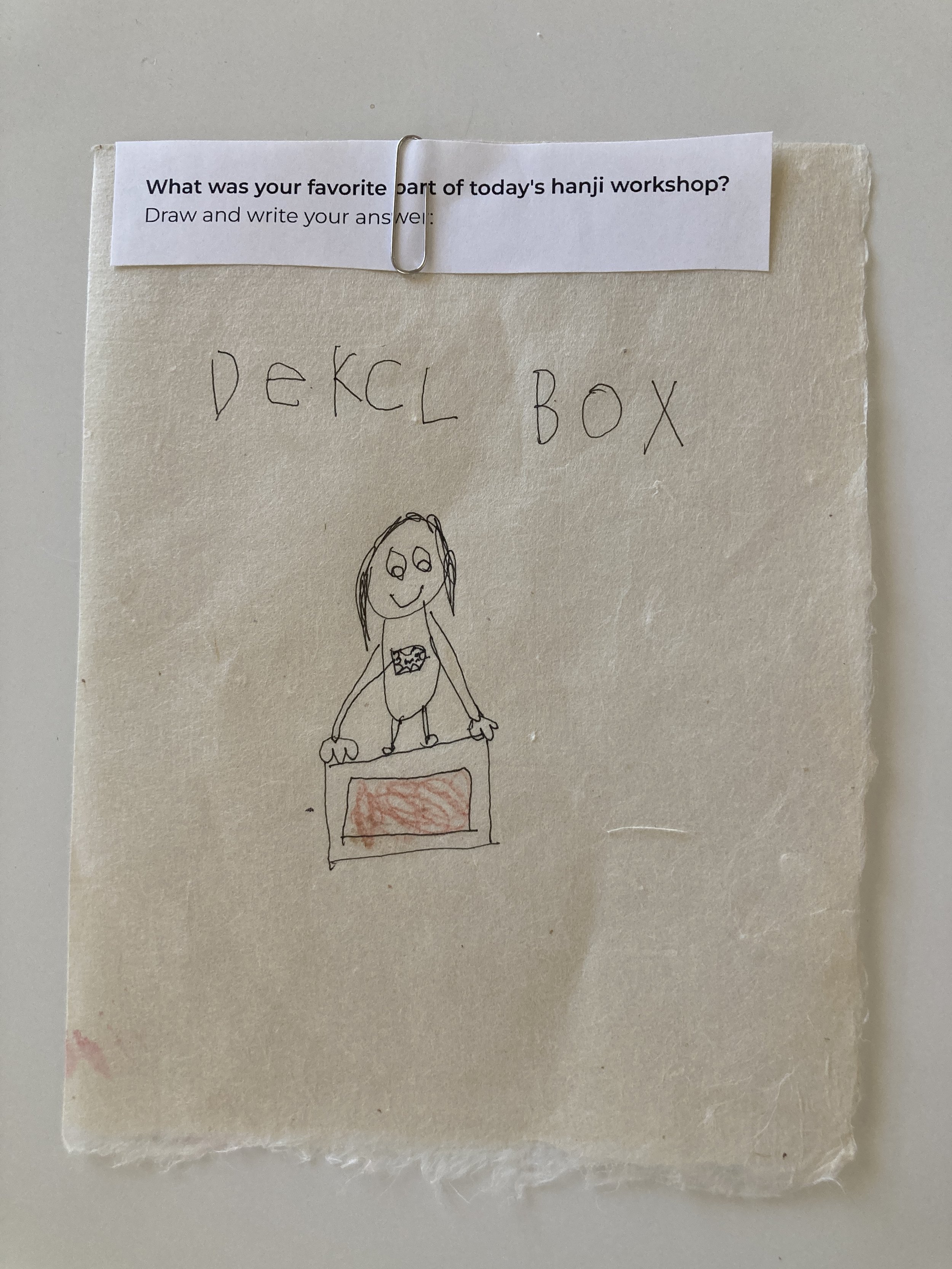

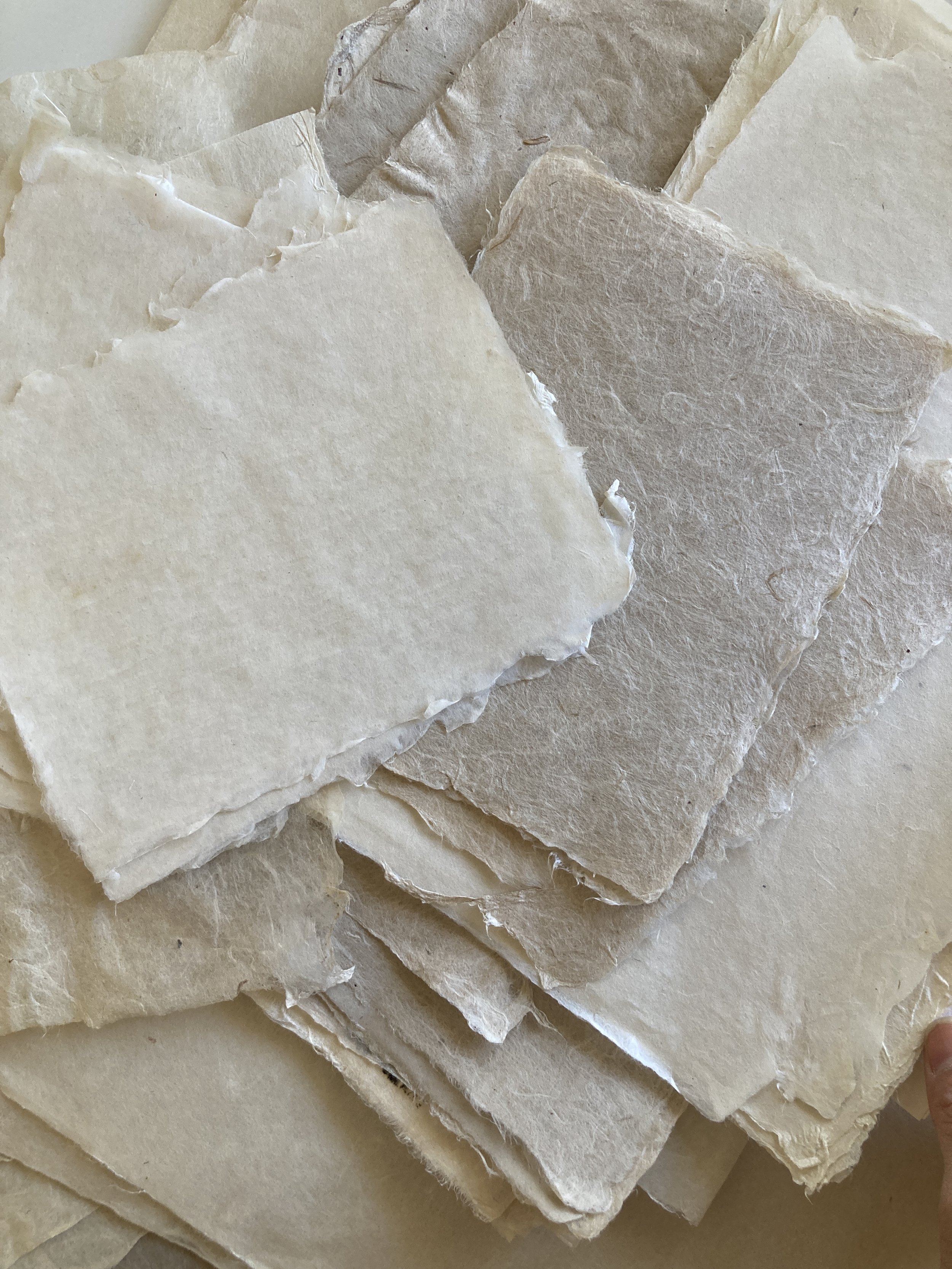

That Reclaiming Us session on lineage was a few days after my late-night ER visit. After we did the visualization, I felt compelled to write messages to myself on strips of hanji and then twist and ply the strips into cords. The last time I had made hanji cords in earnest was over 10 years ago at a hanji workshop with Aimee Lee at a book art conference in Oregon. At that time I remember deciding that I would never make hanji cords again because it was too hard / I wasn't good enough at it, even though I enjoyed doing it. But with the image of the tule cord still in my mind, and the experience of making fresh tule cord still in my body, I went with it, as awkward as it felt to revisit this abandoned process with paper. I made a hanji cord and wore it around my wrist that night, and it felt like an opening.

Hanji cord that I made out of strips with messages that I wrote during the Reclaiming Us session

That night I decided that I would make hanji cord bracelets for the Winter Faire. I had been researching other craft supplies to buy like wooden beads and pom poms to make snowmen or some other typical wintery Waldorf craft, and then thought, why not just make more hanji cords. It's not like I don't have drawers and drawers of hanji, and what better use for it. This would be a good way to practice and I wouldn't have to spend any money. I recalled the last time I visited my hanji teacher Jang Seongwoo with Winnie in 2023. Along with showing us some of his jiseung treasures, he taught Winnie how to knot a bracelet out of hanji cord:

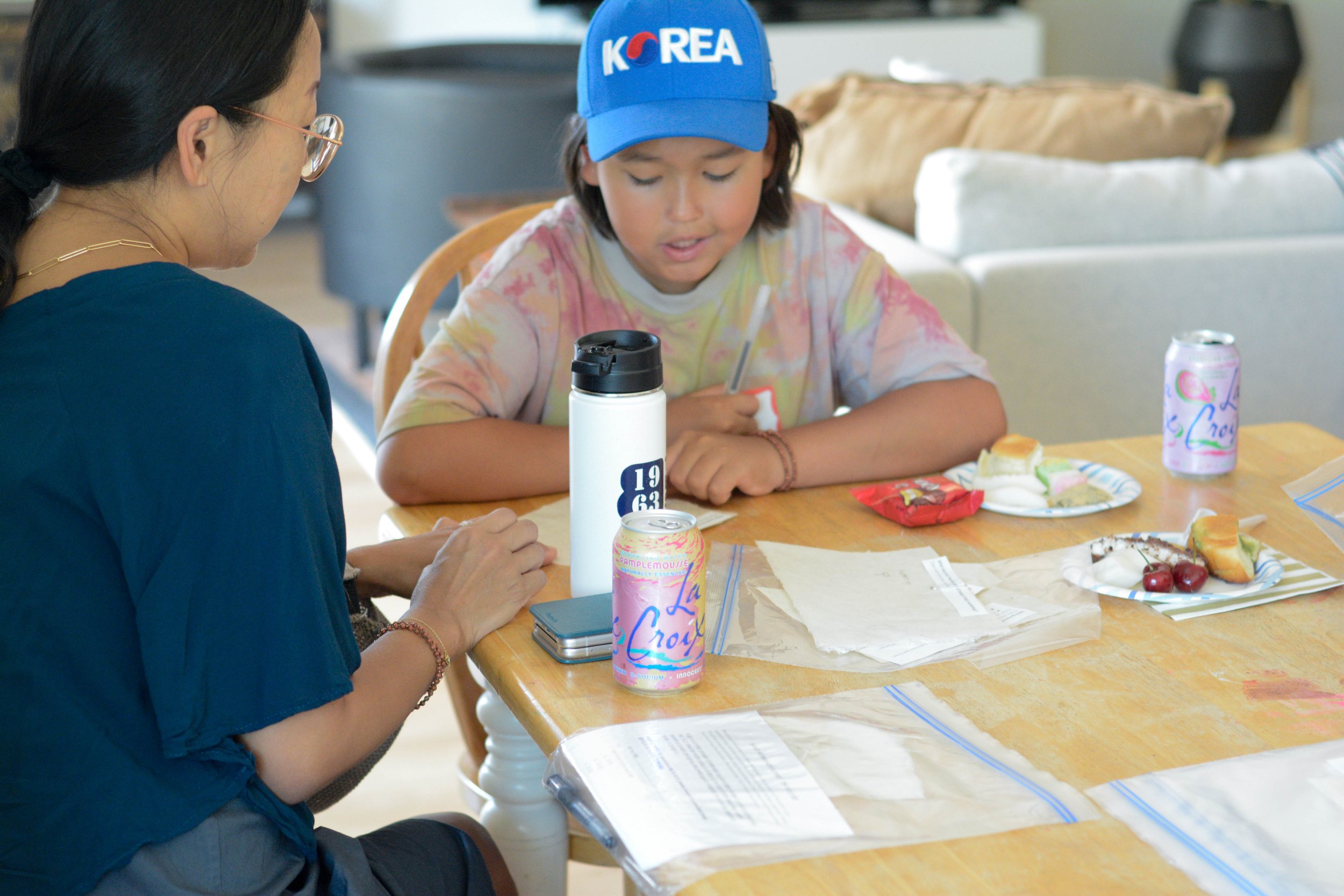

I thought I would just make the cords myself and then have my kids help me dye them. But when I told Winnie the plan, she wanted to learn how to do it. Soon she was quickly making cords, albeit a bit uneven and lopsided, but I know with practice she will someday soon surpass me.

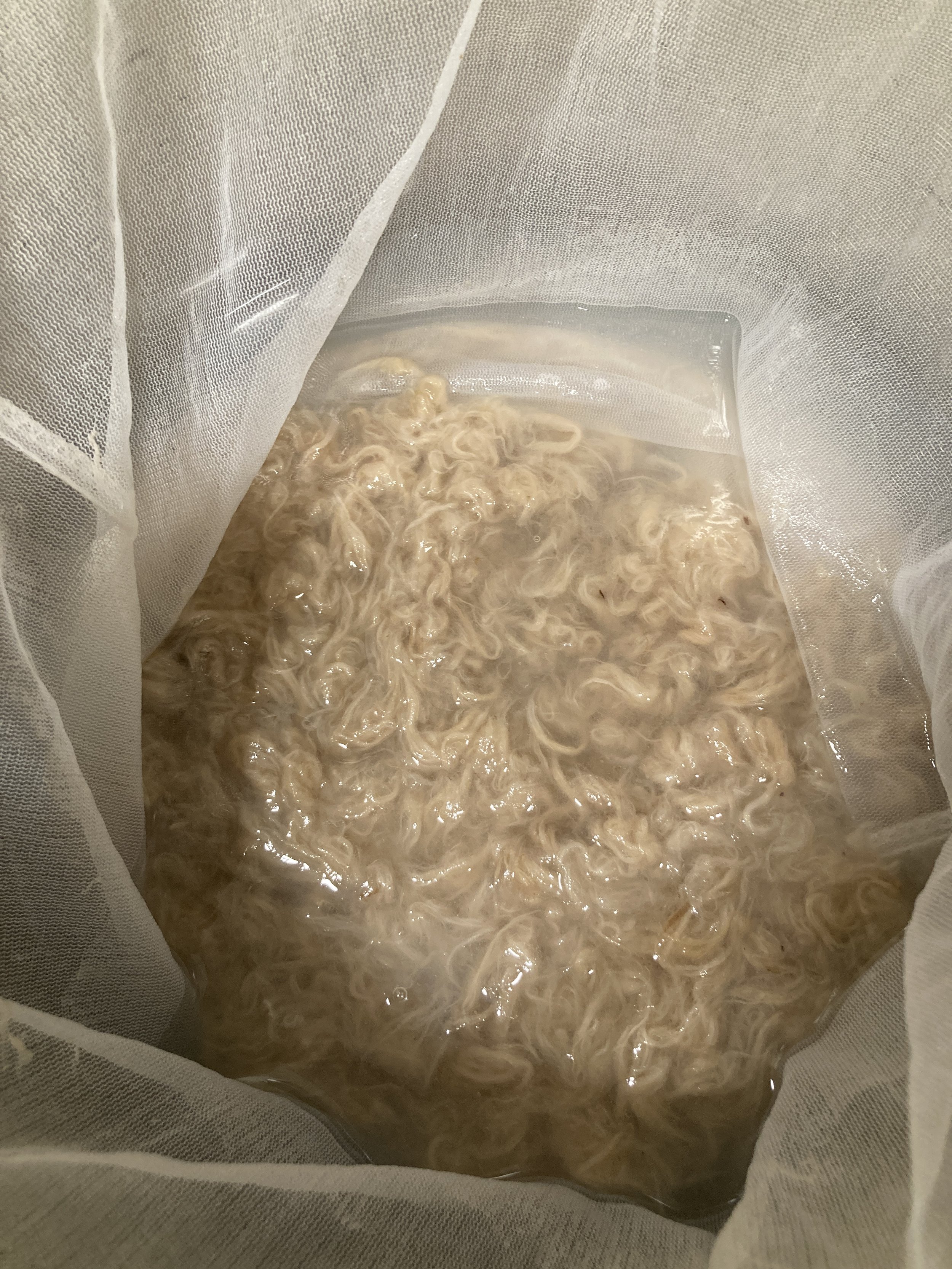

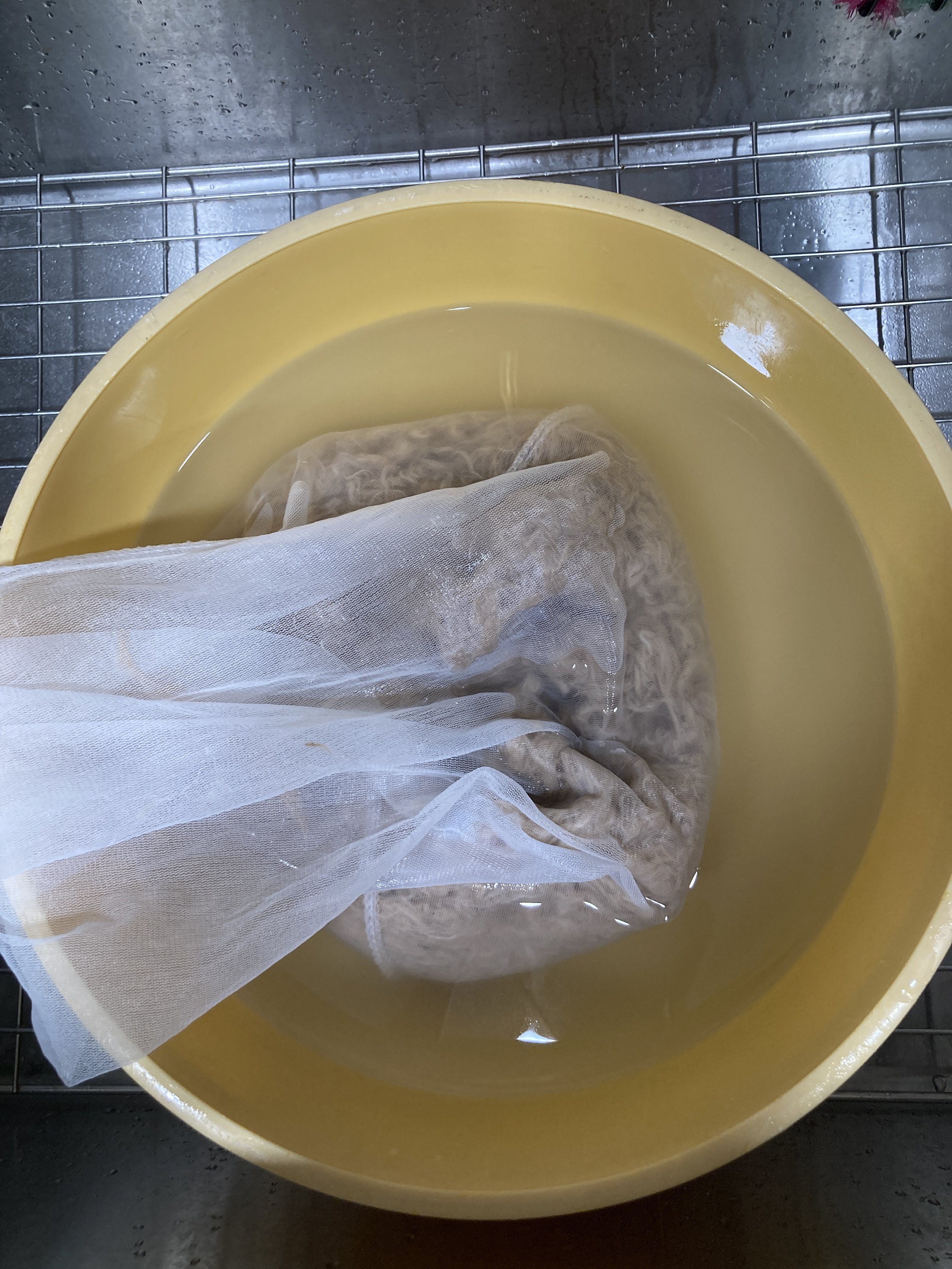

We worked on the cords over several days during Thanksgiving break and finally had enough to move onto dyeing:

About 50 hanji cords that we made over several evenings

We dyed them different colors: cochineal for pink and orange, red cabbage for blue, 치자 (gardenia fruit) for yellow, and old logwood for brown.

Finished hanji cords: dyed, dried, mordanted with alum, dried, then dyed again

On Thanksgiving day, my mom came over and helped me knot the cords into bracelets while Daniel took the kids out for a couple hours. We sat at the table quietly knotting. I asked her about her hometown (상주, near 대구), about my dad's hometown (a small town near 청주). I shared how we don't observe Korean rituals like jesa, bowing to ancestors, because of Christianity and how as a result, I feel so disconnected from my lineage. I shared how I wish to develop a relationship with my ancestors and we discussed where in my house would be a good place to set up an altar. I treasure that conversation, as much as I grieve the loss of similar conversations with my father, who, pre-stroke, would always oblige when I would ask about his childhood years. The pain I experienced at the ER connected me to my grandmother, to my mother. It was an opening, a door.

After Thanksgiving break, I put all the finished bracelets in a ziplock bag and dropped them off at the front office at my kids’ school. The bracelets looked small and unassuming, with no indication of the manual labor or intergenerational pain that went into their making. It reminds me of the labor and skill required to make strong and delicate sheets of hanji, and then somebody mistaking it for a paper towel. (Yes, this happened to me before.) Does the final product and its end use truly matter? No, and yes. None of it matters, and all of it matters. I think about the local tatreez circles hosted by Dana, a Palestinian tatreez artist. I attended a couple this past year. We were encouraged to bring whatever tatreez we were working on. The point was the power and cultural significance of tatreez as a distinctly Palestinian craft form. The point was the power of gathering in resistance, using our hands to stitch and our bodies to support one another in community. My tatreez work is beginner-level, it is not high craft, but it is important, it elicits joy, and it tells a story.

Winnie smiling and running in her hanbok at her school’s Winter Faire

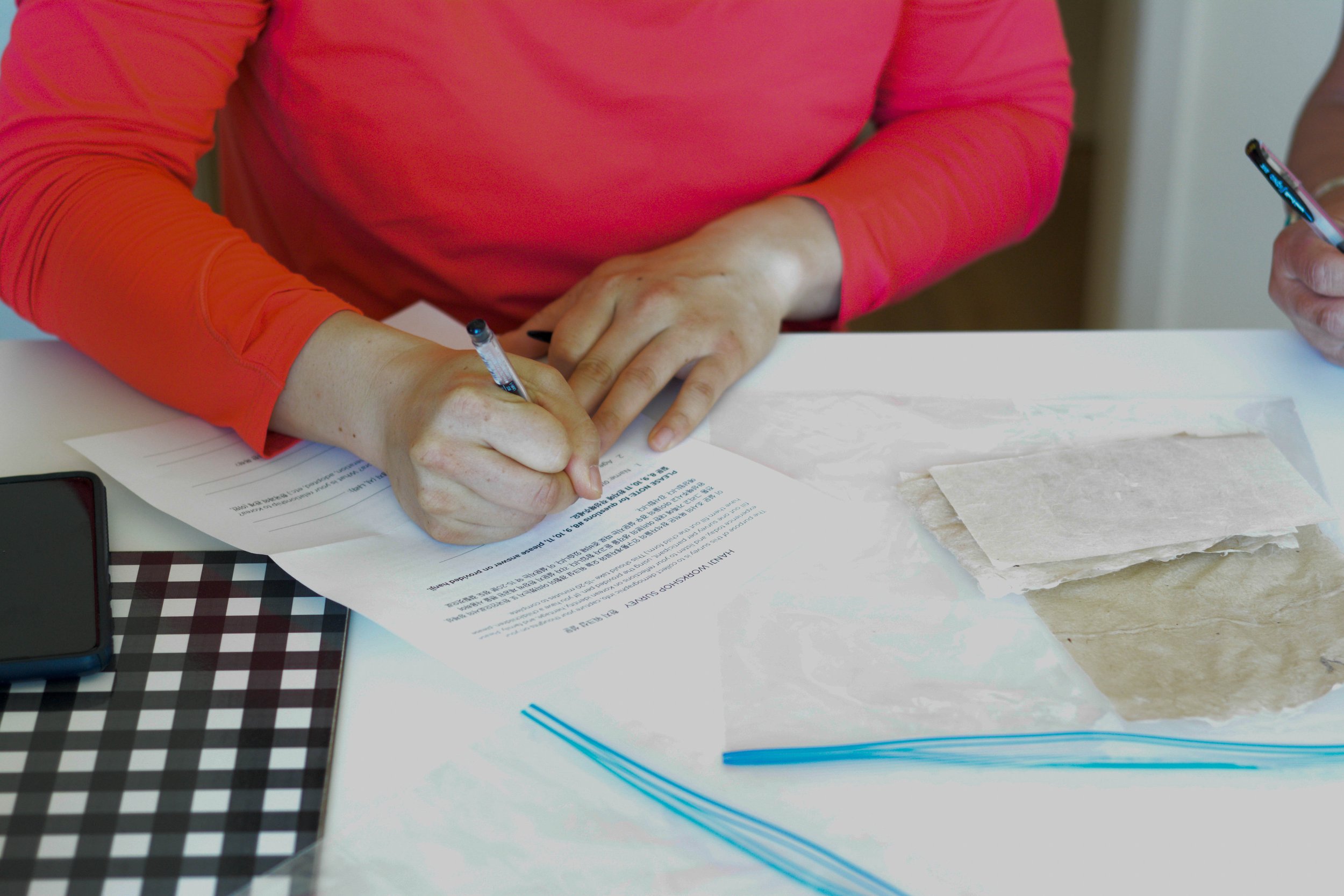

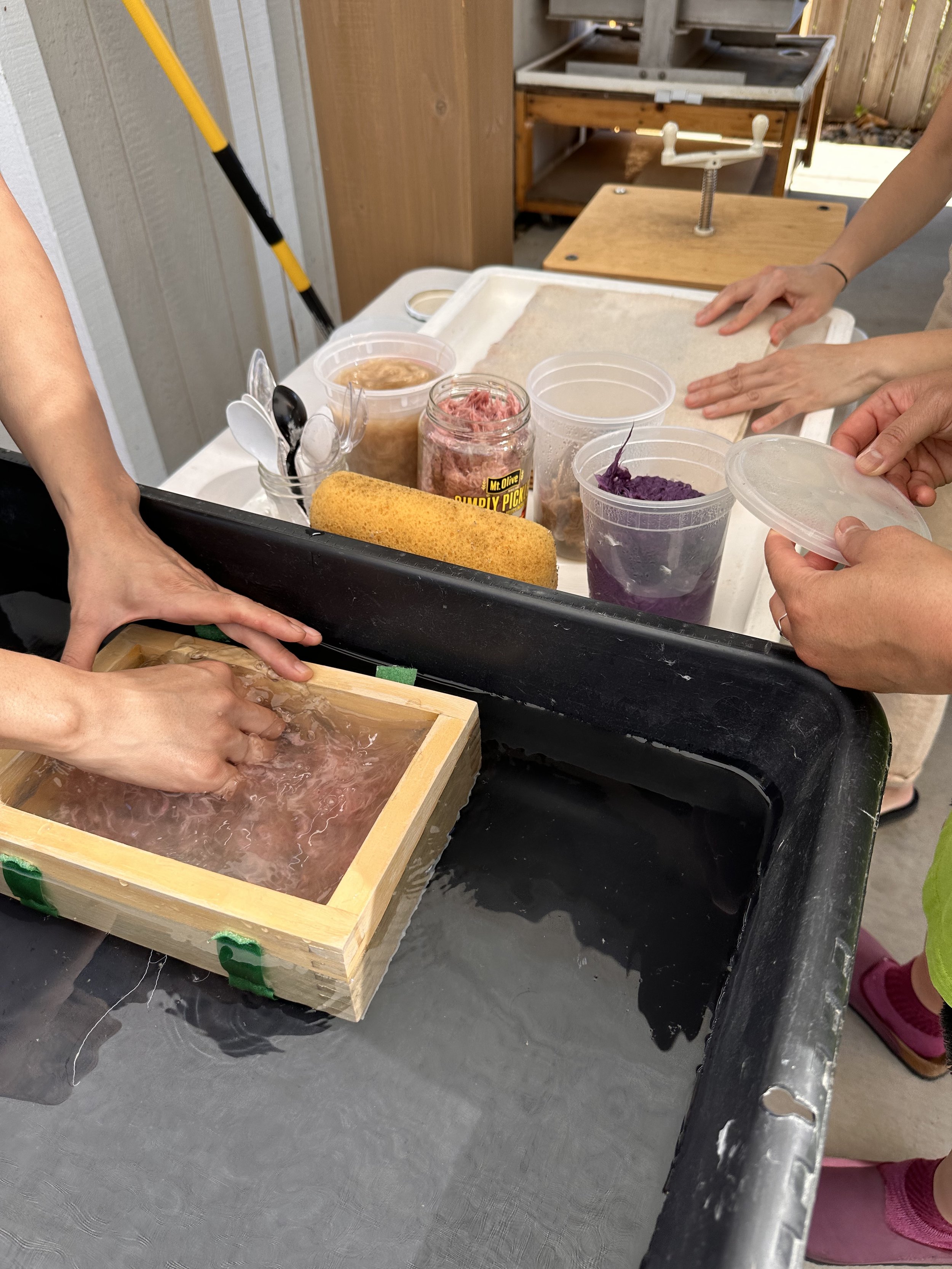

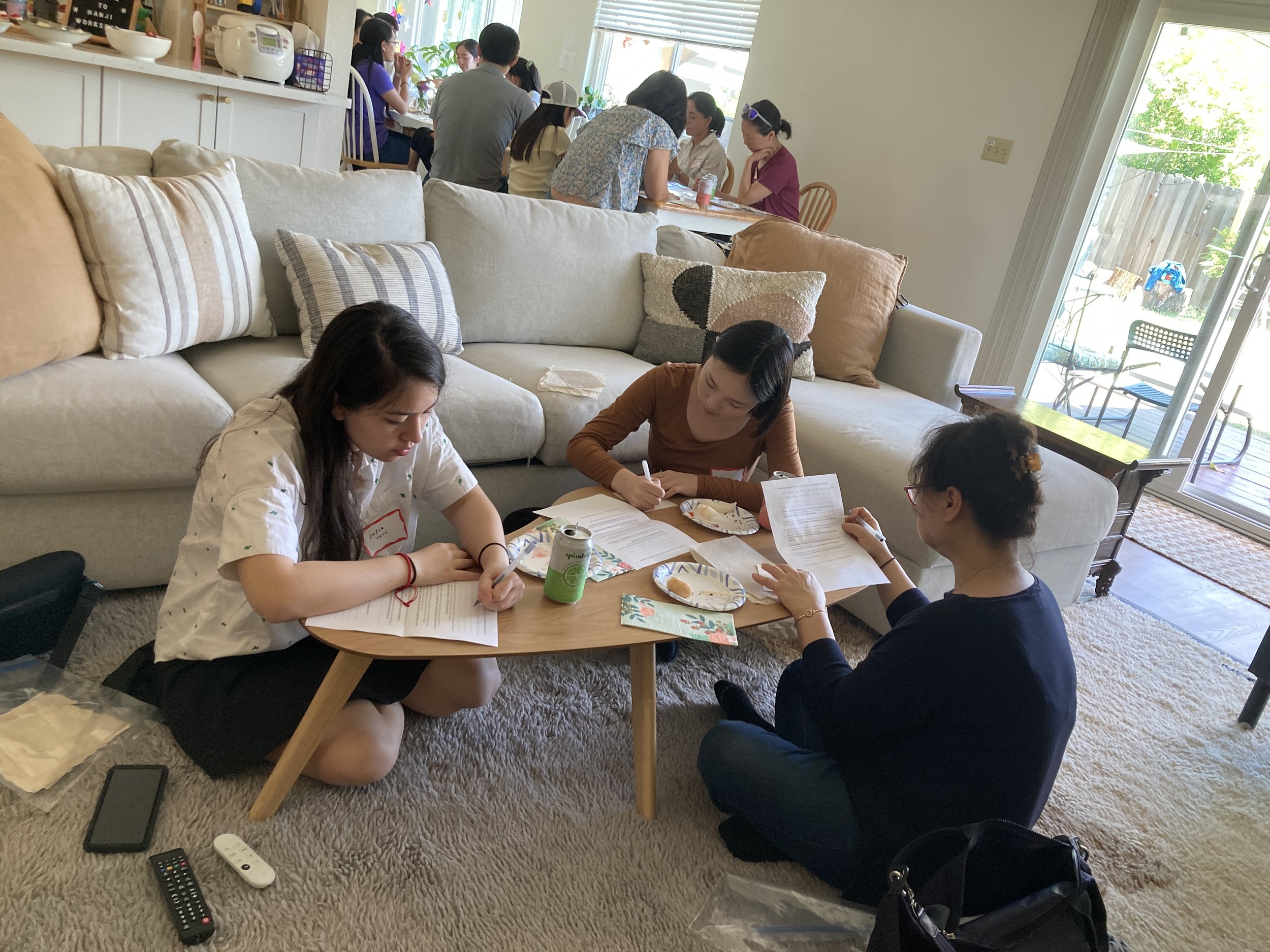

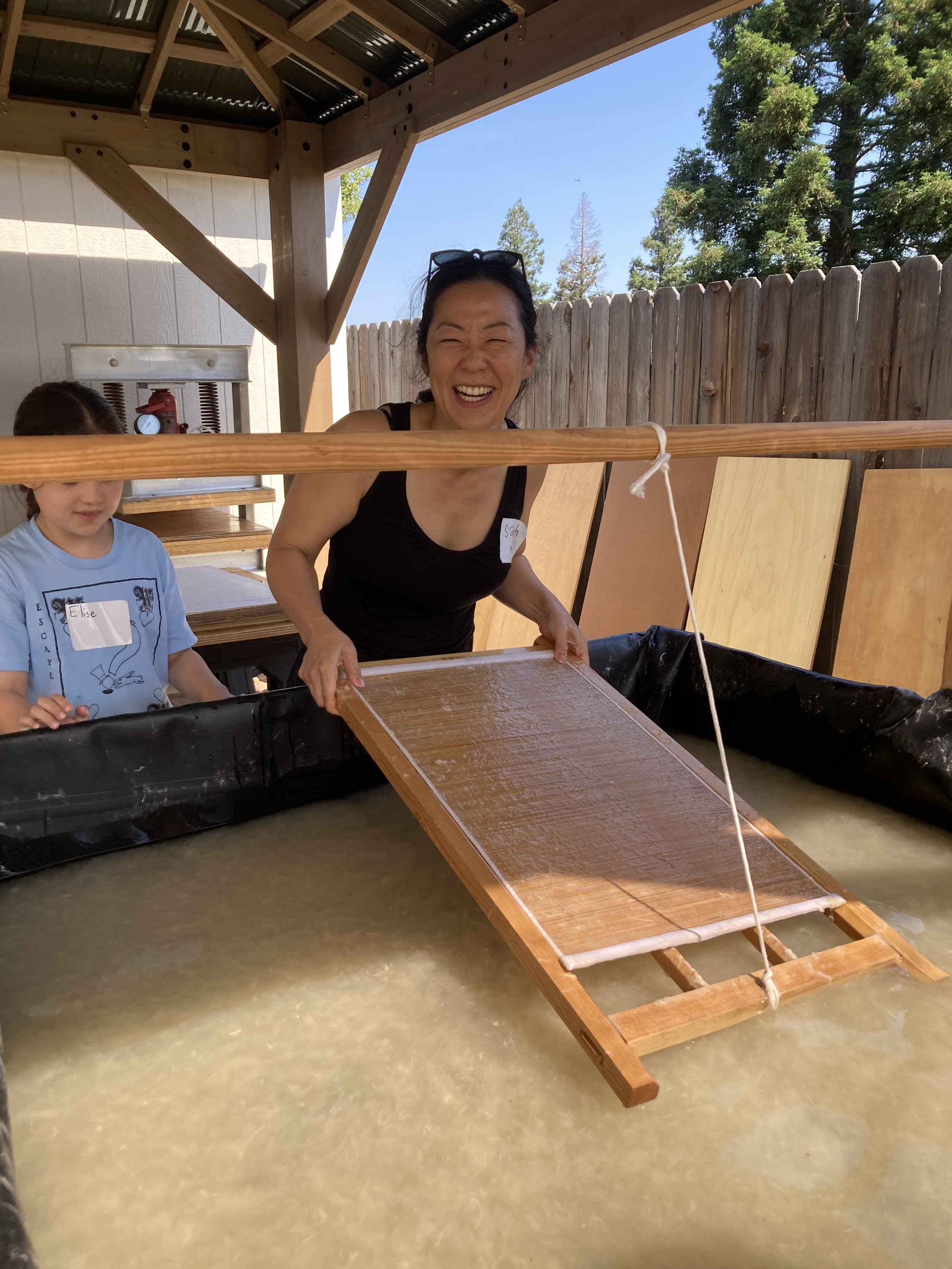

Post-election, I decided to offer a couple free community gatherings at my house. I felt a strong urge to gather with others, to share and not hoard my knowledge. To offer a space of skill sharing, connection, and mutuality. It felt important and necessary. The first gathering led to a beautiful papermaking day which I wrote about here. The second gathering was all about cordage, and I invited Tanya to share about tule cordage and her own experiments with making cord out of silk and other materials.

Twelve of us gathered and shared about cordage from various cultures. Tanya brought silks that she dyed the night before along with a generous pile of fabric scraps. She shared about the Tending and Gathering Garden at Cache Creek Conservancy and her relationship with Diana and tule. We experimented with making cords out of various materials, including flax paper, fabric scraps, giant wool off cuts, even recycled produce bags. I shared how to cut down hanji into strips and how to twist and ply the strips into cords. We dyed our hanji cords with walnut dye that Michelle had brought. It was experimental play, it was joyful and meaningful work. I am thankful for the openings this season that have led me on this path. I believe it has been for my healing and growth, and I continue to listen and look for the signs, starting with my own hands, my own body.